Modern C++, as defined in the C++11 standard has evolved to become an algorithmic language. This represents as much an idiomatic departure from Object Orientation as C++ was a departure from C’s procedural top-down composition. “C++11 feels like a new language,” says Bjarne Stroustrup [Stroustrup]. The primary focus of modern C++ has become algorithms and generic programming. To this end, the language absorbs a number of idioms from other languages and paradigms, ranging from functional to meta programming concepts. Incidentally this is also the realm in which a much older language has done exceedingly well — since the 1950s: Lisp. Lisp is not only the first implementation of the Lambda Calculus but its entire structure is optimised to make generic programming easier. This paper will explore how the high level approach to developing programs in C++ is increasingly shaped by some of the same forces that dominate in developing programs using Lisp.

Given that our premise is that modern C++ has departed from an object-oriented, type based focus and refocused on algorithm and generic programming, I thought it appropriate to start with some quotes from one the key author of the STL, Alexander Stepanov. In an interview on stlport.org, Stepanov is attributed the following statements [Stepanov]:

“STL, in a sense, is an application of generic programming techniques that Dave Musser and I have been developing to a C machine model.“

The interesting point to note is that the basis of his design is C, not C++ and therefore not Object Orientation. Stepanov is indeed somewhat hostile towards the latter.

“Yes. STL is not object-oriented. I think that object orientedness is almost as much of a hoax as Artificial Intelligence.“

Stephanov’s position may be summarized as: instead of finding algorithms to embed in types, abstract the algorithms to operate across types.

“Yes. Always start with algorithms.“

Incidentally, algorithms are the idiomatic starting point when developing systems in Lisp. Scheme, a dialect of Lisp, in particular is said to be an “algorithmic language.” In fact Scheme’s standard documents are entitled “Revised Report on the Algorithmic Language Scheme.” [Scheme] It borrowed this idea from Algol standards documents.

Stepanov elaborates:

“I suddenly realized that the ability to add numbers in parallel depends on the fact that addition is associative … In other words, I realized that a parallel reduction algorithm is associated with a semigroup structure type. That is the fundamental point: algorithms are defined on algebraic structures.“

Algebraic structure of types in particular is of course one of the tenets of functional programming languages, such as Haskell or the Hindler-Milner family of languages. Stepanov has thus set a course for C++ that departs from both object orientation and implicitly from imperative thinking. A certain degree of impedance mismatch between the various concepts and tenets that make up C++ should therefore come as no surprise.

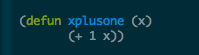

Since Stepanov’s inspiration started with something as simple as addition, we shall follow suit. We will take a simple generic algorithm in both C++ and Lisp as a starting point for our discussion: add 1 to a number x. This is simpler than adding two numbers, but it will suffice for our discussion.

This reads as “define a function” (defun) named “xplusone” which takes one argument “x.” Its value is represented by (equals to) the expression “add 1 to x.” Firstly we note that the algorithmic structure follows the English language structure. This is owing to the use of prefix notation over infix notation. While in English we may talk about the sum of “a” and “b”, in arithmetic we would say “a sum b” or “a + b“. Most programming languages follow the latter, but it’s really a question of your point of reference. Lisp leans towards the meta language coined by the mathematician Haskell Curry: U-language [U-language], an abstraction representing communication from one person to another. This natural language heritage has made Lisp particularly suitable in natural language processing and symbolic computation and one might say that the root of algorithms is the manipulation of symbols [Algorithm]. Consequently, we might expect the synergy between Lisp and algorithmic programming to be a deep one. With that difference out-of-the-way, let us introduce the C++ equivalent, so we can proceed to more interesting discourse.

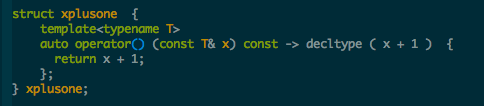

The above implements a functor whose operator() is implemented as a template function. Note how this differs from templating the entire struct and allows us to follow immediately with an instantiation of xplusone without providing the template argument. We can now call xplusone() as we would any ordinary function. The return type of the function is inferred as the result of the expression (x + 1 ). Two observations are striking: 1) The count of curly braces and parenthesis is greater than the Lisp version even though Lisp is known for its pervasive parenthesis. 2) The amount of syntax makes it all but impossible for the untrained eye to see the semantics. A detailed explanation of this C++ code snippet is beyond the scope of this discussion. Instead let us focus on how the Lisp version and C++ versions are used.

Here we define a variable x (defvar) to assume the value 2. We then call xplusone with the value x as argument. Unsurprisingly the value of this expression is 3.

Evaluation proceeds as follows. 2 is an integer. Therefore x is an integer. The sum of 1 ( an integer ) and x is also an integer. Therefore the resulting sum is an integer.

Note how the type has been inferred by way of the type resulting from applying the operator to the operands. Now let us examine the analog in C++.

2 is an integer. Therefore x is an integer. The decltype of ( 2 + 1 ) is also an integer. Therefore y is an integer.

Both C++ and Lisp have proceeded in much the same way. Both implementations represent a generic algorithm that works so long as + is defined for the type of the argument ‘x’ and 1.

Latent Type Errors Deferred to the User

We were fortunate in that there was no need to store state connected with the templated type inside our C++ struct. Had that been the case, we would have had to template the struct in its entirety. Had we, for example, discovered the need to store the value of our calculation inside our struct, our code might have changed thusly.

The implications are profound. The template<> expression has been lifted outside of the struct. We can no longer template just the operator(). This has yielded an incomplete type. xplusone can no longer be instantiated on its own — not without specializing the type. As a consequence the below code compiles perfectly happily.

With the instantiation of xplusone<int> commented out, the compiler has been deprived of the ability to infer if BLAH_BLAH_BLAH… is valid C++. The compiler simply didn’t expand that part of the code. As anyone who has done any complex meta programming in C++ can attest to, this dynamic can play itself out in the most obscure ways. It is often users of the abstractions created through template meta programs who find distant edge cases and are puzzled by compiler errors in subsystems not of their own making. The greater the abstractions, the more this applies. It is especially true when constructing domain specific languages using vehicles like BOOST Proto or working at a similar level of abstraction where incomplete types are layered to form abstractions. Yet even mainstream C++ programmers will attest to the obscurity of error messages deep from the bowels of the STL template library. This latent emergence of type system errors is something ordinarily characteristic of dynamic programming languages. Notable is the difference between run time error detection and compile time error detection. In any case, mechanisms are needed to address this latent emergence of type system errors. If shipping a library of code to a user, it is undesirable for that user to find errors in one’s own product, be they static or dynamic in nature.

We might expect that some measure of effort will be devoted to recover from latent emergence of type errors when developing template meta programs. A discussion of these follows below.

Type Safety Recovery Mechanisms

Let us return to our original examples. In both instances of our definition of xplusone, C++ and Lisp alike, type inference in the compiler has been invoked to complete our program. But the story does not end here. It does not end here, in part, because types have been *implied* through the operators. The loose coupling we have attained in C++ by decoupling ourselves from a polymorphic type hierarchy has been bought at a price: a measure of type safety has been lost. As we shall see, the way the C++ programmer copes with this is much the same as the way the Lisp programmer copes with it.

What do we mean by implied types and a measure of type safety being lost? Let us digress again. What if the function at hand did not operate on numbers to form a sum? What if instead it operated on stack types? Assume further that our C++ model defined a hierarchy of different Stack classes and that we have a function Foo(Stack& s) that takes stacks as arguments? The example is contrived, but contrived to illustrate a point. Assume further that Foo() calls the functions push() and pop() on its stack. In ordinary object orientation, polymorphism will guarantee that only Stack types are admissible, Stack itself or derived classes. After a push() we expect the stack size to have increased by one. After a pop() we expect the stack size to have decreased by one. Type safety ensures us we are operating only on stacks. Indeed in C++11 we may use the delete method mechanism to eliminate even implicit conversion of input arguments to functions. This assures us that nothing may be implicitly converted to a Stack that isn’t a stack. All is well in object-oriented land. The type system is working for us. But what of a templated function Foo() defining an algorithm over stack like types? What if the user provided a “button” type that also implemented “push” with an identical signature? Indeed the compiler would not complain, because the implied interface would also be satisfied. A measure of type safety has been lost that the compiler cannot compensate for. It will be up to the designer of the template function to recover this type safety manually — or live with the ensuing error conditions.

So what might typical mechanisms be to recover type safety? Principally there are four:

- Template specialization

- Type Traits

- Concepts

- Unit Tests

Let us examine each in turn.

Template Specialization

We have already met template specialization. When we wrote…

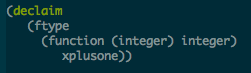

…we completed the type definition of xplusone. You might say, we annotated the template with its type. xplusone is now fully specified. What we are saying here is: we know. We know that this algorithm will work with integers, much the same as declaring a function Foo() to take arguments of type Stack. Nothing is left for the compiler to infer. The problem of type has been solved at compile time. How then does Lisp compare here as a dynamically typed language? Can we similarly annotate xplusone in Lisp ? As it turns out, we can. In the spirit of Haskell Curry’s U-language, we might expect this to read something like the English sentence: “I DECLARE that the TYPE of the FUNCTION xplusone is integer -> integer.” Lisp uses the operators proclaim and declaim for the purpose.

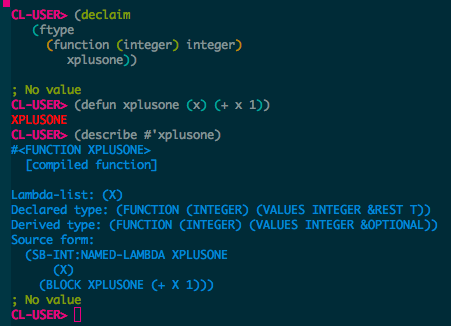

So we have a function that takes an (integer) argument and is itself and integer. We are further saying this relation is a function type and xplusone satisfies is. One thing to note is the correspondence between the manner in which declaim in Lisp and decltype in C++ both declare the type of our expression external to the expression itself. In any event, we have specified the full signature of our algorithm. We may now ask Lisp to describe what it knows about our function.

But what of Lisp’s dynamic nature? Is this not merely an optimization hint? Let’s see. Instead of evaluating xplusone with a non integer type, let us write another function that would violate our type constraints and attempt to compile that.

We note that the type mismatch has been detected at compile type, not at run time. This is because the whole of the Lisp system is available both at run time and compile time, a key feature needed to support Lisp’s macro system. So in principle, features available at runtime can also be made available at compile time. It is up to the implementation how to handle type mismatch conditions. More importantly, it is up to the developer to elicit them.

Type Traits

Type traits are quintessentially predicate logic statements that say something about a type and therefore about instances of that type. For example, a container might require a random access iterator. A type trait might attest to the random access nature of an iterator type. Traits are themselves template types. Their construction proceeds like thusly:

- The unspecialized template returns the default, here false.

- The specialized template overrides that default.

Given the random access iterator example, we might construct a type trait which, unspecialized, returns false and then specialize the trait for random access iterator types to return true. Subsequently we can apply the predicate is_random_access_iterator to template arguments to check if the argument satisfies the random access property. It is clear how this mechanism is well suited to restore some of the type safety that has been lost through templates. Two things are worth noting: we must write these traits where there are not available to us already & we must employ them manually to enjoy their benefit. We are now spending our time recreating type safety that used to work by way of the compiler.

Lisp programmers will know where I am going with this and why I identified traits as being predicates. Lisp has a built-in “system” of predicates. Most are available for the programmer to use out-of-the-box and many more are generated behind the scenes as the programmer defines new types. As a matter of convention, predicates are functions ending in p. Lisp is known to be a symbol computing language, so chiefly concerns itself with symbols. Of interest, for example, might be if a symbol is bound to a definition. If the condition is “bound” our predicate might therefore be “boundp.” Let’s try this.

So in the first instance foo was not bound, so the predicate returned false (NIL). After binding foo to the value 1, foo is bound so “boundp”” returns true (T). Analogously, we can check if our function xplusone is bound. Yes. Maybe someone has already written xplustwo? No.

Simple arithmetic predicates are defined also.

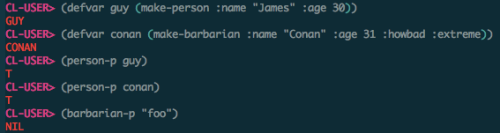

User generated types are automatically equipped with suitable predicates. We create some types to demonstrate:

The macro system will have created common functions, such as constructors called “make-<type>”. We can use our predicates to check for these.

The interface we expected exists for both person and barbarian types. Let’s construct some people and apply the generated predicates to example expressions.

So guy is a person, as is Conan. “foo” is not a person. The onus is on the developer to apply these predicates where appropriate to facilitate type safety.

The onus is on the system to generate commonly used predicates. In practice predicate generation is attained by macros that abstract relevant types. In modern C++, the onus is on the developer to BOTH create type traits AND apply them to attain type safety.

Concepts

Concepts might be thought of as static unit tests embedded inside a template function or template class (unit) which explore if the template argument satisfies the use cases of the template function or class. Concepts exploit the fact that in C++ compilation and linking are two entirely separate phases of constructing an executable. It is therefore possible to write code in a concept that exercises the interface of the template argument and emit meaningful error messages from the interface of a template class or function — rather than getting error messages deep from the inner workings of templated code. This essentially means we can provide meaningful interfaces once more. Because linkable object code does not reference these concepts, they are optimized out by the linker. But because concepts are only compiled, not executed, they are not suitable to verify dynamic properties of a type argument. What is unique about concepts is that they are embedded in the template code.

Lisp’s analog to concepts can be found in macros. See here for an elaboration. Likewise, unit tests may be used to verify the properties of a system. So let us explore unit testing.

Unit Tests

In reverting to our stack example, and in restoring type safety to a function consuming a stack type parameter, what we are really interested in is not if push exists, or if pop exists. It is possible to conceive of a button type that implements both. What we are interested in is if the invariants of a stack hold for the type in question. A push increases element count by one, a pop decrements it by one, and for all popped elements these equate to the last elements pushed. If these properties hold, we need not care what the actual type is. “For all” -> “exhibit property” is a clue that what we really want is a system of universal quantification over some domain of discourse [universal]. We have once more arrived at predicate logic [predicate] and Lisp’s predicate system creates a natural basis for extending proof of correctness into predicate logic. Our approach therefore becomes:

1) Write a unit test in terms of predicate logic that shows required properties hold for type T

2) Statically bind, by way of ftype annotations etc., the function, whose correctness we are trying to prove, to the type T

The above combination in effect subsumes both traits and concepts as type safety recovery mechanism. Notably, we can now roll use cases for traits, concept & unit tests into one using just predicate logic.

This type of check is particularly well suited to the use case for exhaustive pattern matching and algebraic types. In essence, whether or not a particular function has exhaustive coverage for handling an algebraic type is easily explored with a universal quantification based predicate check. We may define generator functions to span the domain of algebraic types like thus:

Interestingly, the library used in the above examples hails from the world of Haskell, so it’s applicability to algebraic types ought to come as no surprise [quickcheck]. What is noteworthy is how Lisp has the ability to absorb distinct paradigms conservatively, by which I mean without forcing them onto the language or the user, but without producing an apparent disjoin. Lisp tends to produce a blend, rather than a disjoin.

Of course, the C++ programmer still has to write unit tests as neither traits nor concepts cover dynamic behaviour, but few designs manage to unify the three. I have seen but one such design during the course of my career.

Performance

Performance was not a focus of this discussion, but somehow it would just not be complete without it. Surely the effort spent by the C++ programmer must confer its benefits. The assumption is that the machine code of the C++ compiler is significantly faster than that emitted by a comparable dynamic language compiler. While this may hold true in general, it does not necessarily hold true with Lisp. Lisp is a programmable programming languages. If we are inclined to program it for speed, we can. Let us start with the disassembly of the xplusone() C++.

Even if you are not accustomed to reading assembly, it is fairly straightforward to interpret what is happening here. Firstly “push” sets up the call stack, register operations to move data into place, followed by a call to a native “add” instruction, and concluded by a pop unwinding the stack and finally a “retq” returning from the function call. Now let’s look at the equivalent in Lisp. Brace yourself for significantly more boiler plate.

The first “that’s NICE” moment I had when looking at Lisp disassembly was that I noted it was commented. That surely makes it easy to interpret what one is looking at even if one is not an assembler guru. I am not an assembler guru. Ok, observations: we are moving the address of a generic plus function into the R11 register. Then we call that, not a native CPU instruction. Presumably, the generic add function will know to call through to the same native integer arithmetic instruction for integers and defer to floating point arithmetic otherwise. Presumably, it will also have error checking to handle being passed a non number type. The error trap after the return statement implies as much. The C++ version had an advantage here, in order to compile and disassemble, I had to provide type information by invoking with an integer argument. The C++ variant of xplusone simply won’t compile without it. Let us level the playing field.

Unix C++ programmers will be familiar with the gcc optimization options -O1 through -O3. These correspond to optimization levels enabling progressively more optimizations. Lisp too has three such levels. However, it defines these across two dimensions: speed & type safety.

The former is clearly appropriate when using Lisp in a manner akin to Perl or Python, i.e. rapid prototyping & runtime type checks. The latter is appropriate for performance. What is more, we can vary these settings throughout what C++ programmers know as compilation units [attribute]. So rather than these options being passed as command line arguments to the compiler, they are associated with individual forms, at our discretion. Dough Hoyte, in his book “Let over Lambda” gives us some macros to assist with this [efficiency]. These are “slow-progn” & “fast-progn”. This enables us to build abstractions such as the one shown below:

This macro allows us to abstract away the boiler plate shown below which otherwise starts to look nearly as verbose as C++.

And arrive at something like this:

fast-progn may also be represented by the shorthand notation #f [efficiency].

However, in order to appreciate what type of assembly will be generated in calling a particular function, we also need to furnish the system with the function arguments. Looking at the disassembly of xplusone in isolation is not very representative. Being a dynamic compiler, Lisp will do its best to compile xplusone in absence of input type. In short, it will insist on GENERIC-+, at least if we are disassembling from within the REPL. What we really want is a disassembly construct that allows us to judge what machine code will be emitted given a certain input and given the raw expression under consideration. Paraphrased, if I give you and x of type fixnum (an integer) and evaluate the form (+ 1 x), in absence of all other boilerplate, what will you generate ?

Once more, Dough Hoyte provides a macro, simply called “dis”, in Let-Over-Lambda [efficiency]. The below illustrates:

Now we try to improve on this with our fast macro #f.

Voila. One add, two mov, clear carry, pop & return. This is as good as it gets in C. Aside from one type annotation and one optimization annotation, the expression itself has not changed.

Conclusion

Modern C++ has shifted focus from an emphasis on type ( objects ) which accommodate algorithm to an emphasis on algorithms parametrized over types. This mirrors the paradigm of other algorithmic languages, such as Lisp or Scheme. The vehicle C++ has chosen is templates or type parameterization, yielding a loose coupling of algorithm and type. In doing so, C++ is incurring some of the same problems revolving around latent type errors normally encountered in dynamically typed, algorithmic languages, and is adopting similar styled remedies. We call these remedies Type Safety Recovery Mechanisms.

As a general rule, the amount of boilerplate code the C++ programmer will generate to employ these mechanisms will by far outweigh the effort spent by his/her Lisp counterpart. More importantly, the mechanisms the C++ programmer will use are disjoint rather than building naturally on each other, which has a tendency to yield gaps in the design. Verifying that these gaps don’t exist should be the focus of any design effort in this context.

We have observed that the flexibility of loose coupling between algorithm and type in C++, while it confers benefits of a flexible design, also creates work surrounding the type system. Might this paradigm be appropriate in some situations then and less appropriate in others? Or should we use it everywhere and at all times? The answer is likely to revolve around the dynamics of the Expression Problem [expression] in that if :

a) Your type system evolves rapidly but your algorithms are largely constant, costs will outweight benefits

b) Your algorithms evolve rapidly but your type system is largely constant, your benefits will outweigh costs

In other words, the answer is not to be found in the system specification, but rather in the problem domain and successfully predicting if the type aspects or the algorithm aspects of the problem domain will change quicker and more substantially.

Knowledge of advanced Lisp will help you foresee where cracks in mainstream C++ designs will emerge before these cracks become apparent to C++ programmers.

References

[Stroustrup] http://isocpp.org/tour

[Algorithm] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algorithm

[Stepanov] http://www.stlport.org/resources/StepanovUSA.html

[Scheme] http://www.r6rs.org/

[U-language] http://cahiers.kingston.ac.uk/concepts/metalanguage.html

http://letoverlambda.com/textmode.cl/guest/chap1.html

[universal] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_quantification

[predicate] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predicate_logic

[quickcheck] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QuickCheck

[attribute] gcc allows function level optimization options by way of _attribute__((optimize("-O3")))

[efficiency] http://letoverlambda.com/index.cl/toc “Macro Efficiency Topics”

[expression] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expression_problem

Lisp can perform the type of checking found in the Concepts section. Since the type system supports complex boolean clauses and the type inference does not make a static declaration about the value of a variable across its entire usage, various branches and different code paths can assume distinct types which change across tests & usages.

This is a great article. I’ve been going through the 4th edition of Stroustrup’s C++ book that covers C++11. Having not looked at C++ for over 10 years and having spent many of those years with Common Lisp, 2 things stood out. (1) C++ is approaching Common Lisp and (2) the amount of text required to accomplish this is painful. Witness Greenspun’s tenth.

I’ve seen at least 3 different programming styles within C++. #1 is the C with classes style, where it’s mostly just C, but with sparse use of classes and other C++ extensions. #2 is the more Java approach, that leans more heavily on polymorphism and less on templates. Style #3 is the one described here, that’s approaching the level of type generic programming that’s possible with Haskell or Lisp.

For me, I don’t see the point of style #3, when MUCH better systems exist– code is verbose, obtuse, not as type safe as it should be, and confusingly dislocated. I’ve seen beautiful and useful libraries / systems built with style #2, for example, the Qt library, or Chromium. I don’t really understand why style #3 is more pervasive in the “official” channels of the language, such as the STL and C++11. C++11 introduces some things that make working with the STL easier, but it’s *still* painful compared to other languages.

Your C++ examples are unnecessarily verbose. The first uses OOP style, which is absent from your Lisp code. It should be shortened to:

template

auto xplusone(const T& value) {

return value + 1;

}

Your minimum C++ program should be shorter too (no data is being read from the outside world):

void main() {

auto x = 2;

auto y = xplusone(2);

}

Thank you for your feedback. I think I was striving for the functor idiom in my C++ example. This gives me an assignable function object as might be used, for example, in STL higher order functions. Lisp gives me all that for free essentially with just the defun construct without requiring explicit reference to the Common Lisp Object Model (CLOS). So borrowing OOP was indeed to get equivalent functional style as offered by the Lisp version. I do concede that this is not how I put either the C++ functor or the Lisp defun to use in my example as I stopped with type derivation. So, yes, one could drop the C++ functor, but it would no longer be equivalent to the abstraction created by the Lisp version. To be fair, std::function does allow “capture” of free functions, so I could use that in effect to get my assignable function objects back – I prefer not to use these in that std::function must be explicitly typed when std::function is instantiated. This tends to spread the function definition around in a way that does not happen with either the Lisp defun or the C++ functor model.

“Actually I made up the term “object-oriented”, and I can tell you I did not have C++ in mind.” – Alan Kay

“I’m sorry that I long ago coined the term “objects” for this topic because it gets many people to focus on the lesser idea. The big idea is “messaging” – Alan Kay ( http://lists.squeakfoundation.org/pipermail/squeak-dev/1998-October/017019.html )

“I think that object orientedness is almost as much of a hoax as Artificial Intelligence.“ – Alexander Stepanov

Object orientedness in C++, and any other so-called object-oriented language without messaging, *IS* a hoax.

Incidentally, message passing as used for example in the Actor Model employed by Erlang and Scala is one of the mechanisms used to make an architecture laterally scalable. Lateral scalability is precisely the challenge faced by object orientation as the shared memory model hits a wall in the multi-core age.

Pingback: Thoughts on C++ and Common Lisp | Rudy Neeser

I programmed in C++ from 1993-2003, C# 2002-2008. Python after that and the last 18 months have been Clojure so it is interesting reading your article. I am not sure what would bring me back to C++ but I am impressed with the innovations. The other language I am learning now is Julia. I am very curious to see how C++11 does and if it can win back a larger audience again. Clojure is basically unknown but I have found it to be a great programming language for many things. It still has the legacy issues with the JVM (poor at taking advantage of multiple cores, poor at floating point accuracy). Your article was very detailed and gave me hope that the language is going to move in a direction I will like.

Really nice article, thanks! You mention that Lisp provides type information in the compile and run time, then compare to C++ meta-programming techniques with type traits and Boost concepts, have you considered C++ RTTI to be included in the comparison?

BTW, please have a look at the latest Stroustrup proposal on Concepts Lite – http://isocpp.org/blog/2013/02/concepts-lite-constraining-templates-with-predicates-andrew-sutton-bjarne-s — this *probably* is going to be included in one of the C++0y incarnations.

C++ is old and crufty and it is rapidly being replaced by more powerful and sophisticated languages like Javascript.

If C++ was any good, it would be C++ which is running inside our browsers and not Javascript.

C++ is actually reasonably adept at absorbing different paradigms. “Old”, “crufty” or “any good” are perhaps oversimplifications. Inside a browser you would expect to run a script language and C++ is not a scripting language. Lisp too is adept at absorbing different paradigms. The chief difference is that with Lisp these feel “well rounded,” because with macros none of the previous language features are fixed. Thus as new paradigms are brought on board, old a paradigms are “moulded into place.” CLOS is perhaps the most classic example of this. C++ is different in this regard. It is constantly hampered by the need to be backwards compatible. So as new paradigms are brought on board, they often feel awkward, sort of like juggling scissors. Bartosz Milewski has a beautiful write-up on this at this URL http://bartoszmilewski.com/2013/09/19/edward-chands/

Neither C++ nor Lisp are purist in their approach. This differentiates them from other languages such as Haskell which take one single paradigm and project it across every aspect of the language. The latter is is very powerful in that it eliminates entire classes of errors otherwise made in mainstream programming languages but it becomes equally restrictive – adapting to other paradigms becomes unfeasible, by design. As times goes on more pragmatic languages adopt the features and innovations from newer, “purist” languages and in doing so reduce the incentive for the average developer to embark on learning the “purist” language to obtain its alleged benefits. The trouble is that the more pragmatic mainstream language becomes more complex and sometimes less well rounded in the process. This is the point where Lisp really shines. It’s entire grammar and structure is optimised to being malleable. This means precisely that it is able to adapt where others cannot.

Most software is not algorithmic which is why we dont use functional languages in 90% of software. You could build a lisp that only cared about mapping an eschewed algorythms, ignore type systems altogether and have a better solution that both.

I use C++ daily and I use its “algorithmic features” near enough daily. The assessment that 90% of software is not built that way is also correct. 90% of software is also not re-usable. It is rather a chicken-egg question if this means that the functional paradigm does not scale up to most real world use cases or if it means most development falls short of the mathematical rigour required by the functional paradigm…

Languages like C++ associate the type with the variable.

Languages like lisp associate the type with the data.

So, by analogy, C++ makes “television boxes” which can only

contain televisions. Lisp make boxes that contain anything.

Unless you’re programming C++ with void* everywhere

you are not being at all lisp-like.

Lisp allows generic programming and so does C++. As demonstrated in the article, both can formulate generic functions. The starting point of each is different. The analogy of a television box typifies the container class of a variable; that memory location which may contain a type of thing. This is rather the starting point of C++ and, in the end, every generic template expression is reduced to that. And yes, Lisp does not do that. Yet, as demonstrated, it is equally possible to constrain type in Lisp, in a manner of speaking both at compile and at run time. So Lisp starts with the generic form and allows restricting type while C++ starts with the “memory box” and allows templates for “generic boxes.” The point of the article was rather that this means a good Lisp programmer can foresee where a C++ programmer will face difficulty, both at a micro level and a macro level, when adopting generic programming techniques.

What about taking a look at generic lambdas and return type deduction… look this sample for example http://stackoverflow.com/a/23142715.

thank you so much for writing. this is a well-thought and useful article.

Pingback: Lambda-Over-Lambda in C++14 | thoughts...

Pingback: Modern C++ and Lisp Programming Style | ExtendTree

Pingback: Visto nel Web – 280 | Ok, panico

Typo at https://chriskohlhepp.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/screen-shot-2014-04-08-at-5-23-32-pm.png

should read xplusone(x) rather than xplusone(2).

Thank you Joe!